The Arikara are an Indian tribe of the northern group of the Caddoan linguistic family. In language, they differ only dialectically from the Pawnee. The name Arikara means “horn, referring the tribe’s former custom of wearing the hair with two pieces of bone standing up like horns on each side of their heads.

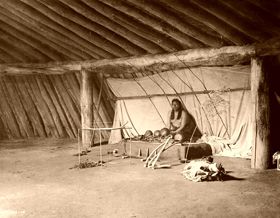

Arikara Indian at the alter, by Edward Curtis, 1908

When the Arikara left the body of their kindred in the southwest they were associated with the Skidi, one of the tribes of the Pawnee confederacy. Tradition and history indicate that at some point in the broad Missouri Valley the Skidi and Arikara parted, the former settling on the Loup River in Nebraska and the latter, continuing northeast where they built on the bluffs of the Missouri River, villages of which traces have been noted nearly as far south as Omaha.

The Arikara are an Indian tribe of the northern group of the Caddoan linguistic family. In language, they differ only dialectically from the Pawnee. The name Arikara means “horn, referring the tribe’s former custom of wearing the hair with two pieces of bone standing up like horns on each side of their heads.

When the Arikara left the body of their kindred in the southwest they were associated with the Skidi, one of the tribes of the Pawnee confederacy. Tradition and history indicate that at some point in the broad Missouri Valley the Skidi and Arikara parted, the former settling on the Loup River in Nebraska and the latter, continuing northeast where they built on the bluffs of the Missouri River, villages of which traces have been noted nearly as far south as Omaha.

In their northward movement, they encountered members of the Sioux making their way westward. Wars ensued, with intervals of peace and even of an alliance between the tribes. When the white race reached the Missouri River they found the region inhabited by Siouan tribes, who said the old village sites had once been occupied by the Arikara.

In 1770 French traders established relations with the Arikara, below Cheyenne River, on the Missouri River. Lewis and Clark met the tribe 35 years later, reduced in numbers and living in three villages between Grand and Cannonball Rivers, South Dakota. By 1851 they had moved up to the vicinity of Heart River. The steady westward pressure of the colonists, together with their policy of fomenting intertribal wars, caused the continual displacement of many native communities, a condition that bore heavily on the semi sedentary tribes, like the Arikara, who lived in villages and cultivated the soil. Almost continuous warfare with aggressive tribes, together with the ravages of smallpox during the latter half of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th centuries, nearly exterminated some of their villages. The weakened survivors consolidated to form new, necessarily composite villages, so that much of their ancient organization was greatly modified or ceased to exist. It was during this period of stress that the Arikara became close neighbors and, finally, allies of the Mandan and Hidasta. In 1804, when Lewis and Clark visited the Arikara, they were disposed to be friendly to the United States, but, owing to intrigues incident to the rivalry between trading companies, which brought suffering to the Indians, they became hostile.

In 1823 the Arikara attacked an American trader’s boats, killing 13 men and wounding others. This led to a conflict with the United States, referred to as the Arikara War, but peace was finally concluded. In consequence of these troubles and the failure of crops for two successive years, the tribe abandoned their villages on the Missouri River and joined the Skidi on the Loup River in Nebraska, where they remained two years.

However, the animosity which the Arikara displayed toward the white race made them dangerous and unwelcome neighbors, so that they were requested to go back to the Missouri River. Under their first treaty, in 1825, they acknowledged the supremacy of the National Government over the land and the people, agreed to trade only with American citizens, whose life and property they were pledged to protect and to refer all difficulties for final settlement to the United States.

After the close of the Mexican American War, a commission was sent by the Government to define the territories claimed by the tribes living north of Mexico, between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains. In the treaty made at Ft. Laramie in 1851, with the Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa, the land claimed by these tribes in North Dakota to the Yellowstone River, and up the latter to the mouth of the Powder River in Montana; then southeast to the headwaters of the Little Missouri River in Wyoming, and skirting the Black Hills to the head of Heart River and down that stream to its junction with the Missouri River.

Owing to the non-ratification of this treaty, the landed rights of the Arikara remained unsettled until 1880, when, by Executive Order, their present reservation was set apart; which included a trading post, established in 1845, and named for Bartholomew Berthold, an Austrian founder of the American Fur Company.

The Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa together share this land and are frequently spoken of, from the name of their reservation, as Fort Berthold Indians.

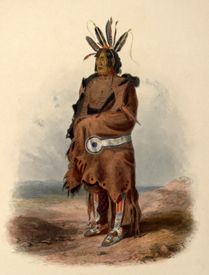

Arikara Maiden

In accordance with the act of February 8, 1887, the Arikara received allotments of land in severalty, and, on approval of the allotments by the Secretary of the Interior on July 10, 1900, they became citizens of the United States and subject to the laws of North Dakota.

An industrial boarding school and three-day schools were maintained by the Government on the Ft Berthold reservation. A mission boarding school and a church were supported by the Congregational Board of Missions. In 1804 Lewis and Clark estimated the population of the Arikara as 2,600, of whom more than 600 were warriors. In 1871 the tribe numbered 1,650; by 1888 they were reduced to 500, and the census of 1904 gave the population as 380.

As far back as their traditions go the Arikara have cultivated the soil, depending for their staple food supply on crops of corn, beans, squashes, and pumpkins. In the sign language, the Arikara are designated as “corn eaters,” the movement of the band simulating the act of gnawing the kernels of corn from the cob. They preserved the seed of a peculiar kind of small-eared corn, said to be very nutritious and much liked. It is also said that the seed corn was kept tied in a skin and hung up in the lodge near the fireplace, and when the time for planting carne only those kernels showing signs of germination were used.

The Arikara bartered corn with the Cheyenne and other tribes for buffalo robes, skins, and meat, and exchanged these with the traders for cloth, cooking utensils, guns, etc. Early dealings with the traders were carried on by the women. The Arikara hunted the buffalo in winter, returning to their village in the early spring, where they spent the time before planting in dressing the pelts.

Their fish supply was obtained by means of basket traps. They were expert swimmers and ventured to capture buffalo that were disabled in the water as the herd was crossing the river. Their wood supply was obtained from the river; when the ice broke up in the spring the Indians leaped on the cakes, attached cords to the trees that were whirling down the rapid current, and hauled them ashore. Men, women, and the older children engaged in this exciting work, and although they sometimes fell and were swept downstream, their dexterity and courage generally prevented serious accident.

Their boats were made of a single buffalo skin stretched, hair side in, over a frame of willows bent round like a basket and tied to a hoop 3 or 4 feet in diameter. The boat could easily be transported by a woman and would carry three men across the Missouri River with tolerable safety.

Before the coming of traders the Arikara made their cooking utensils of pottery; mortars for pounding corn were made with much labor from stone; hoes were fashioned from the shoulder-blades of the buffalo and the elk; spoons were shaped from the horns of the buffalo and the mountain sheep; brooms and brushes were made of stiff, coarse grass; knives were chipped from flint, and spears and arrowheads from horn and flint; for splitting wood, wedges of horn were used.

Whistles were constructed to imitate the bleat of the antelope or the call of the elk, and served as decoys; popguns and other toys were contrived for the children and flageolets for the amusement of young men. Garments were embroidered with dyed porcupine quills; tooth shells from the pacific were prized as ornaments. Also noteworthy was the skill of the Arikara in melting glass and pouring it into molds to form high colored beads used for trade. Their basket weaving has been identified with one practiced by former tribes in Louisiana and probably survived from their ancestors who migrated from the far southwest.

The Arikara were equally tenacious of their language, even though they were next-door neighbors to the Sioux tribes for more than a century, living on terms of intimacy and intermarrying to a great extent. At the turn of the century, almost every member of each tribe understood the language of the other tribes, yet spoke his own most fluently. At this time they also adhered to their ancient form of dwellings, erecting, at the cost of great labor, earth lodges that were generally grouped about an open space in the center of the village, often quite close together, and usually occupied by two or three families. Each village generally contained a lodge of unusual size, in which ceremonies, dances, and other festivities took place. The religious ceremonies, in which the individuals subscribed or village had its special part, bound the people together by common beliefs, traditions, teachings, and supplications that centered on the desire for long life, food, and safety.

In 1835 Prince Maximilian of Wied, the German explorer and naturalist, noticed that the hunters did not load on their horses the meat obtained by the chase, but carried it on their heads and backs, often so transporting it from a great distance. The man who could carry the heaviest burden sometimes gave his meat to the poor, in deference to their traditional teaching that “the Lord of life told the Arikara that if they gave to the poor in this manner, and laid burdens on themselves, they would be successful in all their undertakings."

In the series of rites, which began in the early spring when the thunder first sounded, corn held a prominent place. The ear was used as an emblem and was addressed as “Mother.” Some of these ceremonial ears of corn had been preserved for generations and were treasured with reverent care. Offerings were made, rituals sung, and feasts held when the ceremonies took place. Rites were observed when the maize was planted, at certain stages of its growth, and when it was harvested. Ceremonially associated with maize were other sacred objects, which were kept in a special case or shrine. Among these were the skins of certain birds of significance and seven gourd rattles that marked the movements of the seasons.

Elaborate rituals and ceremonies attended the opening of this shrine and the exhibition of its contents, which were symbolic of the forces that make and keep all things alive and fruitful. Aside from these ceremonies there were other quasi-religious gatherings in which feats of jugglery were performed, for the Arikara, like their kindred the Pawnee, were noted for their slight of hand skills.

The dead were placed in a sitting posture, wrapped in skins, and buried in mound graves. The property, except such personal belongings as were interred with the body, was distributed among the kindred, the family tracing descent through the mother.

The Arikara were a loosely organized confederacy of sub-tribes, each of which had its separate village and distinctive name, few of which have been preserved.

The following names were noted during the middle of the 19th century:

Hachepiriinu (Young Dogs)

Hia (Band of Cree), Hosukhaunu (Foolish Dogs), Hosukhaunukare rihn (Little Foolish Dogs’), Sukhutit (Black Mouths), Kaka (Band of Crows), Okos (Band of Bulls)

& Paushuk (Band of Cut-throats’)

Today, the Arikara are a part of the Mandan, Hidasta and Arikara Nation, located in New Town, North Dakota.

Information retrieved from: https://www.legendsofamerica.com/na-arikara/2/